National News

As rumors spin on social media, revelers in one of New York City’s most popular neighborhoods for nightlife are on higher alert.

By Remy Tumin and Michael Levenson, New York Times Service

NEW YORK — Revelers streamed into the Brooklyn Mirage on a recent weekend to the steady pulse of electronic music. Diplo, the Grammy-winning DJ playing that night, was not the only thing on their minds.

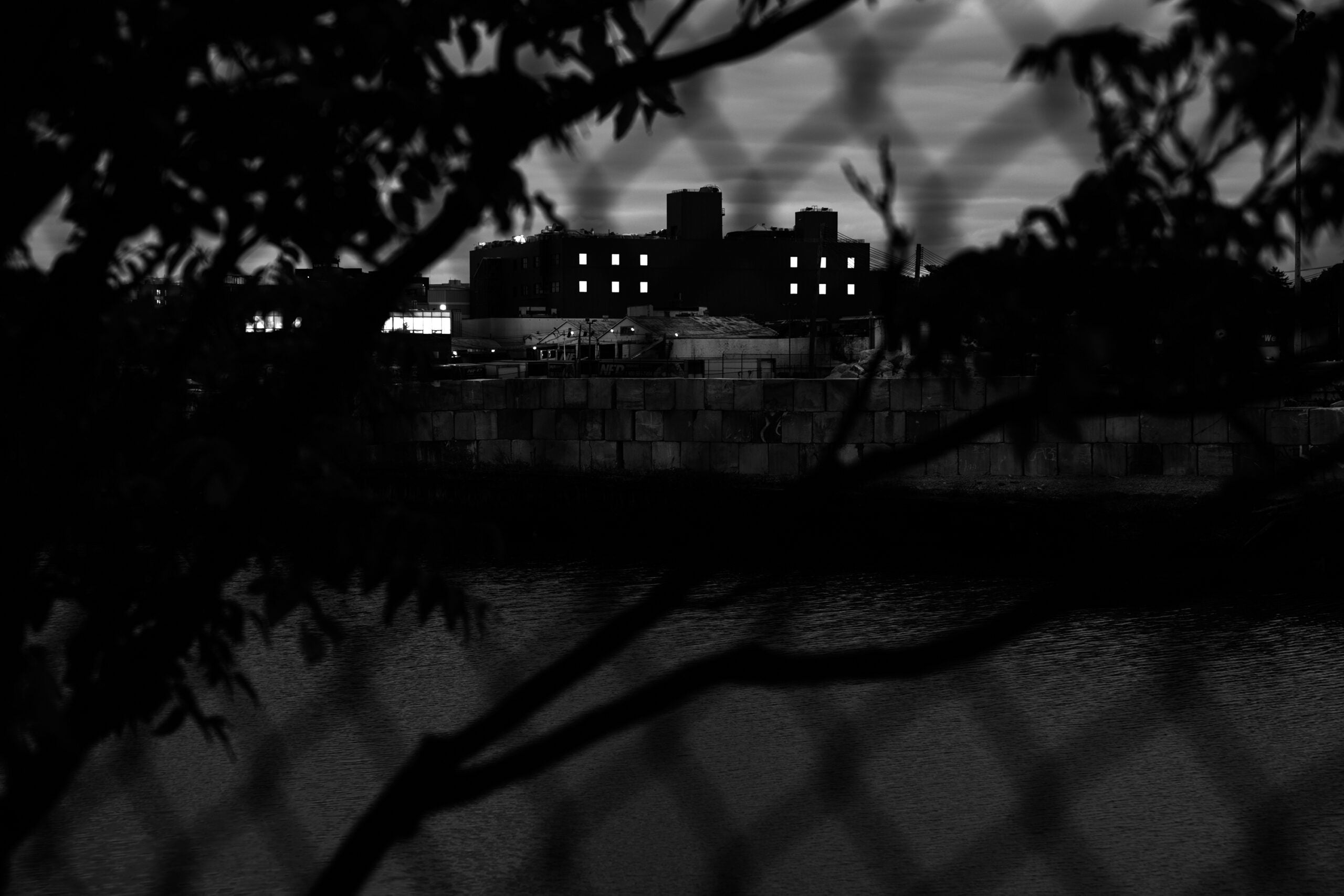

Fans had made their way past waste facilities, lumber yards and tire shops in this corner of East Williamsburg, across a train track and pockmarked streets, chipped away by trucks. Cellphone service is spotty. Streetlights are scattered. Public transit is a 15-minute walk away.

There was a renewed sense of caution after three men who left venues in the area were found dead over the past year.

“We never come alone, and we never leave alone,” said one frequent patron at the Brooklyn Mirage, who would give his name only as Felipe G., 30. “This is an industrial zone. You just don’t know who is here.” He said it was a place to “be smart about your partying.”

The deaths of the three men, whose bodies were found in a creek near the venues, have chilled the nightlife scene in one of the city’s most popular neighborhoods for DJ events and dancing.

Two of the men had been at the Brooklyn Mirage the night they died, and a third was at the nearby Knockdown Center. Speculation has been rampant about a serial killer stalking the area — in TikTok videos viewed hundreds of thousands of times, long threads on discussion boards like Reddit, and even one popular podcast based in Los Angeles. There is a serial killer in Brooklyn, the posts, videos and threads warn.

But there has not been any evidence of foul play in the cases of the two men at the Mirage, police say, and their deaths last year were ruled drownings. The cause of death for the third man, who died this summer, was found to be undetermined.

The investigations have been closed for two of the men, but the gaps in information in the men’s stories still haunt their families and clubgoers. The answers feel unsatisfying, they say, in part because the setting — a sparsely populated area with few witnesses — has made a detailed timeline impossible, and because a night centered on joy and dancing could end so tragically.

Karl Clemente, 27, a case manager at New York City’s child welfare agency, had been hanging with friends at an apartment in Brooklyn in June 2023 before they decided to go to the Mirage. But at the door, security stopped Clemente because he appeared too drunk, and a friend who came outside to look for him found he was already gone, his father, Alex Clemente, said.

Days later, his body was found in Newtown Creek, after his wallet with his credit cards and ID were found at a lumberyard by the water. His death was ruled an accidental drowning. Alcohol and cannabis had been found in his system, his father said.

“It’s very difficult to have no closure at all,” Clemente said.

Weeks later, Zeds Dead was playing at the Mirage when John Castic, 27, a senior analyst at Goldman Sachs, went to see the group. At the show, he told friends he was not feeling well and that he was going to call an Uber to go home, his father said.

But after entering and exiting a car outside the Mirage, Castic did not get an Uber, his father said surveillance video showed.

Instead, he wandered around the neighborhood for 80 minutes and was seen on a bridge pier near Newtown Creek. Castic was found in the water days later, his father said. His death was ruled a drowning.

Ketamine was found in his system, his father said. The New York Police Department said it did not suspect foul play. Still, people on social media around New York City and beyond began to take precautions, warning each other not to go to the venues alone and sharing stories of unnerving occurrences in the area.

Many questioned why it was business as usual at the Mirage.

“The question I would love for them to answer is: What does it take for them to feel something is an emergency?” said Jennifer Gutiérrez, a City Council member whose district includes the parts of the boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens where the venues are.

Then in July of this year, a third man, Damani Alexander, 30, was found dead in the creek.

Alexander had worked security at a Manhattan nightclub, and he often spent weekends with friends around the city, his mother, Desiree Nicholson, said.

Before he died, he had told a friend he was at the Knockdown Center, and sent text messages voicing fear that his life was in danger.

“I think dudes trynna kill me,” one text showed to The New York Times by Nicholson says. “Dudes waiting for me outside,” another says.

The medical examiner said this week that the cause and manner of death for Alexander were undetermined, meaning a doctor, having considered the evidence and test results, could not “make a conclusion with certainty,” the office said.

Nicholson said the police had told her there were no signs of violence and that a toxicology report found cocaine and alcohol in his system, but he did not die of an overdose.

The deaths have fueled baseless rumors online, but locals and visitors say they highlight the need for improved safety in an area where so many go out.

Jonathan Garcia, who goes by Jahno, had met Alexander while working doors at clubs over a decade ago. After his friend’s death, he quit his job working the front door at Elsewhere, a club in the same area.

Getting off work at 4 a.m. just wasn’t worth it anymore, he said.

“Honestly, I was scared,” said Garcia, 31, who had to commute home to Brownsville. “I’ve never felt safe in the area.”

In theory, a desolate industrial neighborhood with few people living nearby would appear to make a perfect location for a dance club — lots of space and few neighbors to bother with noise. That’s why the area, on the border of East Williamsburg and Bushwick in Brooklyn and Maspeth, Queens, has seen a host of venues crop up since the mid-2010s.

Avant Gardner, which houses the Mirage, is Brooklyn’s second-largest venue after Barclays Center.

But in reality, the stretch of North Brooklyn is home to industrial activity 24 hours a day and is bordered by an EPA Superfund site at Newtown Creek.

Still, the area, zoned largely for commercial and industrial use, has drawn in world-renowned musicians to the Mirage, the Knockdown Center, Elsewhere, Silo and 99 Scott, and visitors from across the city and tristate area who come to hear music and go out with their friends.

Alexander had played drums in church and served in the Army, Nicholson said. “He was very lovable, very lovely.”

Castic was eager to meet new friends. “My son was a good-looking, intelligent young man,” his father said. “People not only liked him, they respected his opinion.”

Clemente was “a very loving kid,” who played guitar and was dedicated to his job helping troubled families, his father said. “His passion is to help kids navigate their lives.”

The attention on the clubs has pressured city officials to make changes visitors say were long overdue.

In a widely shared post, Garcia said he wanted to see new fencing around the creek, reduced fares for ride-sharing late at night and a safe place to check self-defense items like pepper spray.

“There are people that can make decisions to make it safer for people like me who go out as a form of therapy,” Garcia said. “If I’m being honest, I need it.”

Over the past year and a half, city officials and the venues have been working to improve lighting and signage, boost cell service and address unlicensed taxi pickups, a spokesperson for the city’s nightlife office said.

The Knockdown Center said it was cooperating with police, and that it was not aware of any continuing threat. “The safety of our public and neighborhood is always a primary priority,” it said in a statement.

Avant Gardner, home to the Mirage, said it was working with city officials to add safety features including increased lighting, designated ride-share pickup areas and staff to direct traffic. “Nothing matters more to Avant Gardner than making sure everyone who visits our venue gets home safely,” the venue said in a statement.

Some of those enhancements have come at the urging of Gutiérrez.

“We have to figure out how to improve so people don’t die,” Gutiérrez said.

For now, staying vigilant depends heavily on patrons.

The rumors did not keep Noelia Soto, 23, from coming to see Diplo recently. Soto and her friends took a train from New Jersey and then the subway to the Brooklyn Mirage. They planned to split an Uber back home.

“Definitely come with a group of people that you trust, not just trust as an extra body, but trust that they’ll take care of you,” said Soto, who frequents the venue. Despite the deaths, Soto said she would keep coming, but with heightened awareness.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

![]()