SEOUL, South Korea — Few people understand what may be going through the minds of North Korean soldiers fighting and dying for Russia in the war against Ukraine. But Lee Chul Eun is one of them.

Lee, 38, a North Korean defector and former soldier now living in South Korea, said it is “devastating” to see troops from the reclusive, communist-ruled North being sent abroad by leader Kim Jong Un, “only to then give up their youth for a land that is not even theirs but the foreign land of Russia.”

He is one of multiple defectors who spoke to NBC News about the training, conditions and mindset of North Korean soldiers, including their willingness to take their own lives if necessary.

Lee said his former colleagues “are essentially just sent out to be cannon fodder on the front lines.”

For the first time since they arrived in Russia in the fall, North Korean soldiers have been captured alive by Ukrainian forces, with video and photos showing one man with bandages around his jawline and another with bandaged hands.Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, who announced the prisoners’ apprehension earlier this month, said they were living proof that North Korea had entered the war, in a major escalation of the yearslong conflict.

The U.S. and allies say there are more than 11,000 North Korean troops fighting in the Russian region of Kursk, where Ukrainian forces launched a cross-border incursion in August. Neither Moscow nor Pyongyang has confirmed the reports.

“Honestly, it is not easy to capture a North Korean soldier,” Ryu Sung Hyu said in an interview in the South Korean capital, Seoul.

All North Korean recruits are taught a song that includes a verse about saving their last bullet for themselves to avoid capture, said Ryu, who served in the North Korean military until 2019, when he escaped to freedom in South Korea.

According to South Korea’s National Intelligence Service, there was at least one recent incident in which a North Korean soldier, faced with possible capture by Ukrainian forces, tried to detonate a grenade while shouting Kim’s name but was killed before he could succeed.

The South Korean military said last week that North Korea is preparing to send additional troops to Russia after about 300 of its soldiers were killed and 2,700 others were injured. The high casualty rate was due to the soldiers’ poor understanding of modern warfare, as well as the way they were being deployed by Russia, South Korean lawmakers said.

Their willingness to fight and die for Russia could be a major factor in determining the course of the Ukraine war, as well as the level of American military aid to Ukraine under President Donald Trump, who has expressed skepticism over continued U.S. support.Kim is thought to be providing Russian President Vladimir Putin with troops and weapons in hope of receiving technical assistance with his nuclear and ballistic missile programs. His flurry of weapons testing has continued with three launches already this year, including multiple short-range ballistic missiles, a new hypersonic intermediate-range missile and strategic cruise missiles.

Trump drew ire from South Korea on Tuesday after he described the reclusive regime as a “nuclear power,” a phrase that U.S. officials have long refrained from using, as it could signal recognition of North Korea as a nuclear-armed state.

Kim is sending troops to Russia for two reasons, “both of which are driven by desperation,” said Ahn Chan Il, who served in the North Korean military for over a decade and defected to South Korea in 1979. The first is to earn foreign currency, which is in short supply in North Korea under United Nations sanctions imposed over its weapons programs.The deployment also provides valuable experience for the North Korean military, which has not been deployed overseas since the Vietnam War.

Dorothy Camille Shea, the deputy U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, told the Security Council this month that fighting alongside Russia makes North Korea “more capable of waging war against its neighbors.”

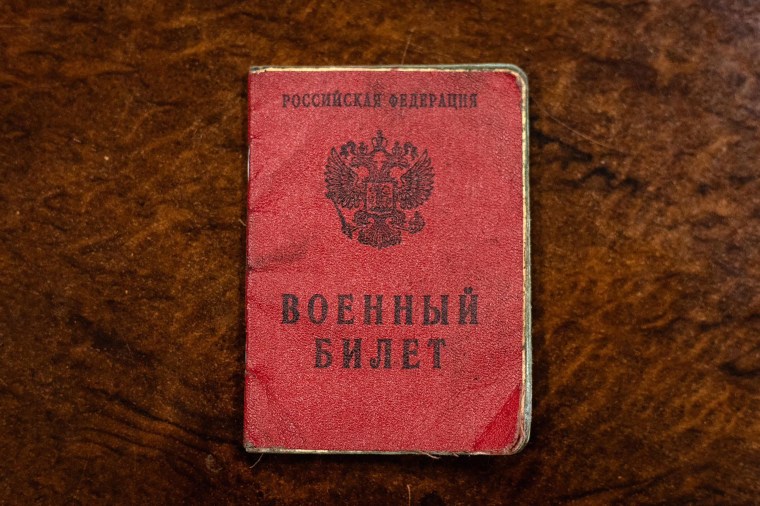

Lee, who spent five years in the North Korean military, said the troops had been sent to Russia as mercenaries rather than soldiers, noting that they weren’t wearing their uniforms. South Korea’s National Intelligence Service has said they were given Russian military uniforms and Russian-made weapons, along with forged identification documents.

“Even if they die there it does not matter, because North Korea sent them out without officially recognizing them,” Lee said. “They were sent there not to bring honor to the country, but to give up their lives and bring back lots of money.”

‘No longer a part of the society’

Military service is compulsory in North Korea, which has one of the world’s largest standing armies. Soldiers undergo three months of basic training before being assigned to a unit, said Lee, who came to South Korea in 2016 after swimming for six hours from the North.

“As soldiers,” Lee said, “they are told they are individuals who are now no longer a part of the society and their families, and must follow the orders of the supreme leader,” meaning Kim.

They have no trouble believing this, having been indoctrinated by North Korean propaganda from childhood, said Lee.

North Korean soldiers spend most of their time not actually being soldiers but working on farms and construction projects, Lee and others said.

“I think I only fired three bullets per year,” said Lee Hyun-seung, who served in the North Korean military for more than three years. When he moved to a more elite unit, he said, “we had more like 20 bullets.”Asked whether he thought the North Korean troops could help Russia win the war, Lee — whose family defected in 2014 and who now lives in the U.S. — was skeptical.

“Honestly, I’m not that sure,” he said, “because I know their training and I know they are not well trained.”

For North Korean soldiers, who receive food and clothing but are otherwise essentially unpaid, the main enemy is hunger.

North Korea struggles with food shortages as Kim devotes the majority of resources to his weapons programs, meaning that, like most of the broader population, soldiers suffer from malnutrition and can even starve to death.

Meals are made up mainly of plain rice, corn or potatoes, sometimes mixed with grass or even tree bark, said Lee Chun Eul.

He said his feelings about North Korea changed gradually, largely due to his exposure to foreign media that finds its way into the country despite tight government controls — “James Bond” was a favorite of his growing up in the 1990s. More recently, the North Korean government has been alarmed by the popularity of South Korean TV dramas, sentencing two teenagers to 12 years of hard labor for watching them.

“When I look at North Korean mercenaries sent to Russia, I wonder if they would still have joined if they had watched as much foreign media as I did in North Korea,” Lee said. “I also wonder if the North Korean regime and Kim Jong Un’s dictatorship would still be in place.”

The defectors say they hope the North Korean troops fighting in Russia will take the opportunity to leave like they did.

“When North Korean workers, who have lived their entire lives trapped in a restrictive system, experience life abroad, they come to see North Korea as nothing short of a prison,” Ahn said. “Once they realize what freedom could mean, it’s hard to imagine they wouldn’t consider breaking free to live a freer life.”In addition to finding freedom, they could provide the U.S. and others with valuable intelligence regarding the North Korean military’s strategies and capabilities, which are often exaggerated by the North Korean government.

Ahn and other North Koreans who defected as soldiers have offered Ukraine their assistance against the North Korean troops.

“However, rather than directly participating in the war, our focus is on psychological warfare to change the mindset of North Korean soldiers,” he said. “Through platforms like YouTube or leaflets, we aim to deliver messages to the North Korean troops, urging them not to die meaningless deaths and instead seek freedom.”

In the meantime, they watch with heavy hearts as casualties mount among North Korean soldiers whose experiences they know only too well.

“These young people did not go knowing they were going to die,” Lee said, “but died because they did not know.

Janis Mackey Frayer and Stella Kim reported from Seoul, South Korea, and Jennifer Jett reported from Hong Kong.

Stella Kim

Stella Kim is an NBC News freelance producer based in Seoul.

Jennifer Jett is the Asia Digital Editor for NBC News, based in Hong Kong.