Unusually dry winter weather meant fires had lots of fuel to burn through, just as strong winds were blowing to spread the flames

Climate change contributed to turning Los Angeles and its surroundings into a dry tinder-box of fuel just at the time of year when strong winds make fire most dangerous, a group of scientists have found.

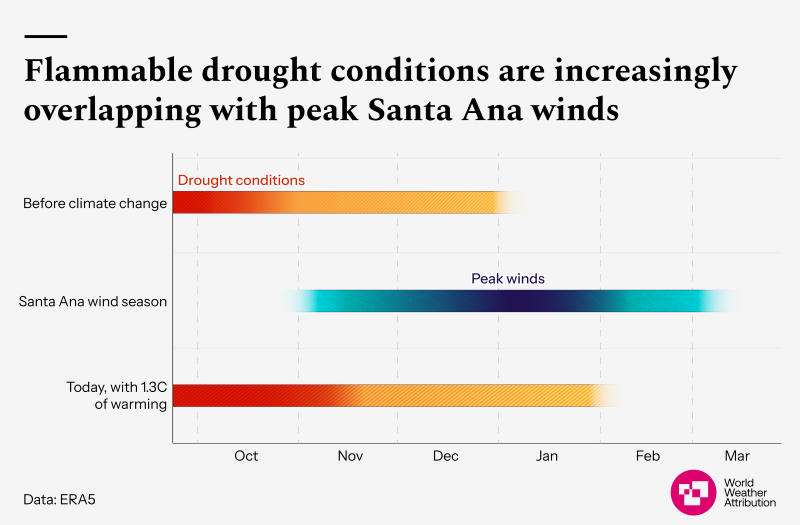

Thirty-two scientists working with the World Weather Attribution (WWA) group found that climate change – resulting in a world 1.3C hotter than pre-industrial times – made the dry conditions that fuelled the fires 35% more likely. A further rise in global warming to 2.6C, which is expected by 2100 on the current path, will make these conditions another 35% more likely again, they added.

“Drought conditions are more frequently pushing into winter, increasing the chance a fire will break out during strong Santa Ana winds that can turn small ignitions into deadly infernos,” said Clair Barnes, a WWA researcher from Imperial College London. “Without a faster transition away from planet-heating fossil fuels, California will continue to get hotter, drier, and more flammable,” she added.

Despite coming to power after the fires’ worst destruction, US President Donald Trump has officially begun the process of leaving the Paris climate agreement, paused all foreign climate finance, promoted fossil fuels and announced restrictions on wind power.

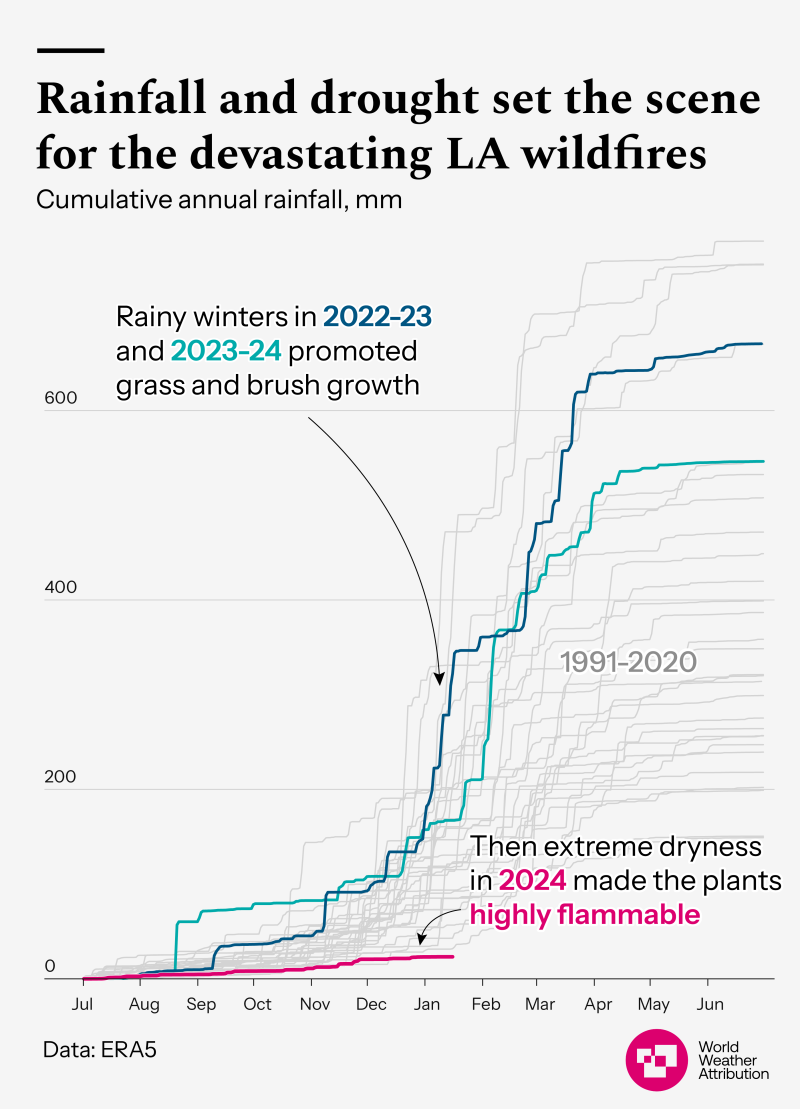

Climate “whiplash effect”

Over the last three weeks, fires around Los Angeles have destroyed over 10,000 homes and killed at least 28 people. While fires in the summer are common in southern California, the winter is usually too wet for fires to spread despite strong winds at that time of year.

But this winter was the driest for over 30 years, affecting the oak trees, shrubs and grasses which surround the city. These dried-out plants fuelled fires which were spread rapidly by high winds and which a fire service with inadequate water supplies struggled to contain, the study found. Fire-prone conditions have lengthened by about 23 extra days each year, the scientists said.

They concluded that, while the extension of the dry season into the windy season is linked to climate change, the role of climate change in the strength of the winds themselves is unclear and requires more research.

While this winter has been dry, the previous two winters were among the rainiest of the last few decades, promoting the growth of the plants which burned this winter. The WWA scientists suggested this may be an example of the climate-driven “whiplash effect”, where very dry and wet weather follow each other, as they did when drought gave way to flooding in East Africa in 2023.

But climate change was not the only factor that worsened the fires in the Los Angeles region. The scientists said that water infrastructure – not designed to fight a rapidly expanding wildfire – was unable to keep up with the scale and extreme needs.

“It was designed for more routine structural fires not the sort of unprecedented and coninuous needs that were posed by the fast moving wildfire that we saw”, said Roop Singh, head of urban and attribution at the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre.

California Governor Gavin Newsom has said that some fire fighters’ hydrants failed because of a lack of water pressure. WWA said that investments in improved pressure management are needed.

The WWA researchers also emphasised the importance of early warning and evacuation systems as 17 of the 28 deaths occurred in West Altadena, a neighborhood where some residents were only advised to leave after the fire had reached the area.

The family of 73-year-old Priscilla Shurney, who died two days after a rushed evacuation, told the LA Times their relative would still be alive if timely warnings had been given.

Park Williams, a geography professor at the University of California, said that while climate change had made the vegetation that served as fuel drier than it would otherwise have been, “the real reason they become disasters is that homes have been built in areas where fast-moving, high-intensity fires are inevitable”.

“Communities can’t build back the same, because it will only be a matter of years before these burned areas are vegetated again and a high potential for fast-moving fire returns to these landscapes,” he added.

Despite warnings like this, many residents have said they will rebuild their burned-down homes – and Newsom has promised to put public money towards reconstruction efforts.

Singh warned that in Los Angeles and globally, there has been an increase in building in the interface between wildlands and cities. She gave the example of the Greek capital Athens, which has a similar Mediterranean climate to southern California and suffered from climate-driven fires this summer.

Trump vows action on disasters

In his inauguration speech on January 20, Trump – a climate change sceptic – said the LA fires had been burning for weeks “without even a token of defense”.

He noted that the disaster had affected “some of the wealthiest and most powerful individuals in our country” who lost their homes to the flames.

“That’s interesting. But we can’t let this happen. Everyone is unable to do anything about it. That’s going to change,” he said, without elaborating on how his government would act.

Later, while visiting storm-hit North Carolina and fire-stricken California, the president said he would sign an executive order to overhaul or get rid of the main federal agency that responds to emergencies, calling it a “disaster” and saying he preferred to give federal money to states to handle catastrophes themselves.

(Reporting by Joe Lo; editing by Megan Rowling)