Civilization’s toughest technical challenges are those that require extraordinary (and constantly improving) performance to be delivered at a low cost. High levels of performance often require complex, difficult-to-produce technology operating close to the limits of what’s possible. Any contractor could put up a five-story building using off-the-shelf building technology, but a 500-story building would be far more difficult to achieve and would require pushing the boundaries of building technology forward to even be possible.

Trying to make something cheap while you’re pushing the boundaries of performance makes things even more difficult. You need to worry about things like minimizing maintenance costs, eliminating expensive materials or components, and having a design that can be manufactured inexpensively and minimizes costly expert labor. (And if you do require expensive components or labor, you need to spread it as thinly as possible.)

Building and operating a leading-edge semiconductor fab is an example of this sort of intersection. The most advanced semiconductors have features that are 1/2000th the width of a human hair and are made from materials where even a few atoms in the wrong place can cause catastrophic defects, thus requiring incredible levels of control and precision during the production process. This control and precision needs to be achieved consistently and continuously, so that transistors can be made in enormous quantities at very low unit costs.

Developing a new commercial aircraft is another example in this category, as is building a cheap, reusable rocket. And so is building a commercial jet engine. With jet engines, performance and economy are closely bound together. To be attractive to airlines an engine needs to be as efficient as possible, minimizing fuel consumption and the amount of maintenance it requires. High fuel efficiency requires high compression ratios and engine temperatures, which in turn require extremely efficient compressors, components that are both incredibly strong and incredibly lightweight, and materials that can withstand extreme temperatures. And a commercial jet engine must successfully operate hour after hour, day after day, for tens of thousands of hours before being overhauled.

Only a small number of organizations are capable of executing such technically difficult projects. Only three companies in the world operate leading edge semiconductor fabs (Samsung, Intel, and TSMC). Depending on how you count, there are just two to four builders of large commercial aircraft (Airbus, Boeing, Embraer, and now COMAC). With reusable rockets, SpaceX is in a category of its own. The number of participants is small partly because of the inherent technical difficulty and partly it’s because success typically requires spending billions of dollars. It takes on the order of $20 billion to build a leading edge semiconductor fab and anywhere from $10 to $30 billion or more to develop a new commercial aircraft.

We see something similar with large commercial jet engines. Only a handful of companies produce them: GE (both independently and via CFM, its partnership with France’s Safran), Pratt and Whitney, and Rolls-Royce.1 Developing a new engine is a multi-billion dollar undertaking. Pratt and Whitney spent an estimated $10 billion (in ~2016 dollars) to develop its geared turbofan and CFM almost certainly spent billions developing its LEAP series of engines. (As with leading edge fabs and commercial aircraft, the technical and economic difficulty of building a commercial jet makes it one area of technology where China still lags. China is working on an engine for its C919, but hasn’t yet succeeded.)

It’s not that building a working commercial jet engine itself is so difficult. It’s that a new engine project is always pushing the boundaries of technological possibility, venturing into new domains — greater power, higher temperatures, higher pressures, new materials — where behaviors are less well understood. Building the understanding required to push jet engine capabilities forward takes time, effort, and expense.

The jet engine was invented in the 1930s, independently by Frank Whittle in the UK and Hans von Ohain in Germany.2 At the time, propeller-driven piston-powered aircraft were capable of traveling around 300-400 miles per hour, but performance gains were getting harder and harder to achieve. At higher speeds, the propeller tips would begin to exceed the speed of sound, creating shockwaves and increasing drag. It was also becoming harder to increase the power of piston engines — as engines got more powerful, they got heavier, offsetting gains in power. Both Whittle and Ohain hypothesized that with an alternative propulsion system, aircraft could achieve much higher speeds and altitudes, and they began to investigate alternatives, ultimately converging on a gas turbine-based propulsion system, or jet engine.

The jet engine is a type of heat engine: it converts heat into useful work. Like a steam turbine or an internal combustion engine, the jet engine works by taking some working fluid (in this case air), compressing it, heating it, and then expanding it, extracting work from the heated fluid in the process.

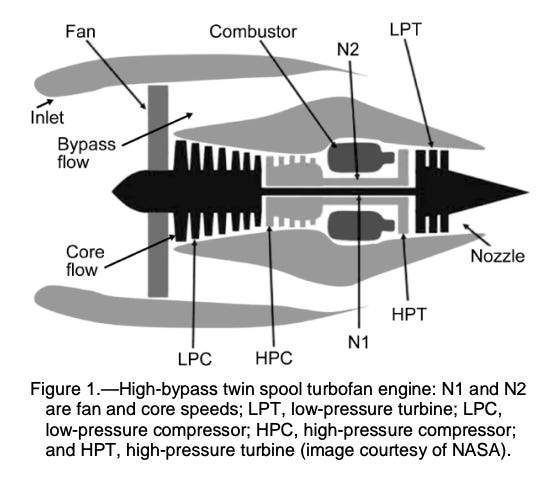

More specifically, a jet engine operates on the Brayton cycle. Air is taken into the front of the engine, then run through a compressor, increasing the air’s pressure. This compressed air flows into a combustion chamber, where it’s mixed with fuel and ignited, producing a stream of hot exhaust gas. This exhaust gas then drives a turbine, which extracts energy from the hot exhaust as it expands, converting it into mechanical energy in the form of the rotating turbine. This mechanical energy is then used to drive the compressor at the front of the turbine.

In a gas turbine power plant, all the useful work is done by the mechanical energy of the rotating turbine. Some mechanical energy drives the compressor, while the remaining energy drives an electric generator. In a jet engine, the energy is used differently: some energy drives the compressor via the turbine, but instead of using the remaining energy to generate electricity, a jet engine uses it to create thrust through hot exhaust gases, pushing the aircraft forward the same way an inflated balloon propels when air rushes out of it.

Building a functional jet engine requires several key supporting technologies. One such technology is the compressor. In a Brayton cycle engine, roughly 50% of the energy extracted from the hot exhaust gas must be used to drive the compressor (this fraction is known as the back work ratio). Because the back work ratio is so large (a steam turbines has a back work ratio closer to 1%), any losses from compressor inefficiencies are proportionally very large as well. This means that a functional jet engine needs turbines and compressors that transfer as much energy as possible without losses. Whittle was successful partly because he built a compressor that ran at 80% efficiency, far better than existing compressors. Many contemporaries believed Whittle would be lucky to get 65% efficiency — jet engine designer Stanley Hooker noted that he “never built a more efficient compressor than Whittle”.

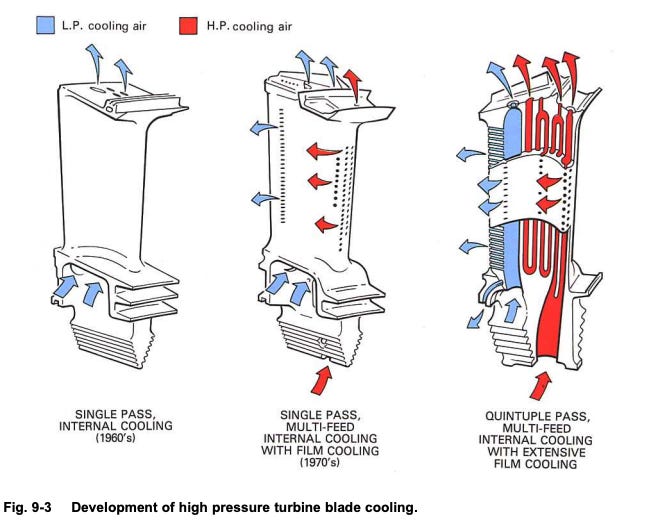

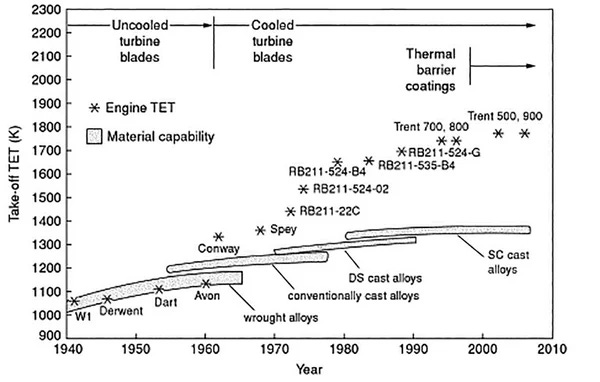

Another important advance was in turbine materials. The fuel in a jet engine burns at thousands of degrees, and the turbine needs to be both strong and heat-resistant to withstand the rotational forces and temperatures. Whittle’s first engine used turbine blades of stainless steel, but these failed frequently and it was realized that stainless steel wasn’t good enough for a production engine. The first production engines used turbine blades made of Nimonic, a nickel-based “superalloy” with much higher temperature resistance. As we’ll see, the need to drive engine temperatures higher and higher has pushed for the development of increasingly elaborate temperature resistant materials and cooling systems.

Von Ohain’s jet engine first flew in August of 1939 (powering the Heinkel He-178), and Whittle’s first flew in May 1941 (on the E.28/39). By the end of WWII both the UK and Germany had fielded several jet powered aircraft including the Gloster Meteor, the de Havilland Vampire, the Messerschmitt Me-262, and the Arado Ar234.

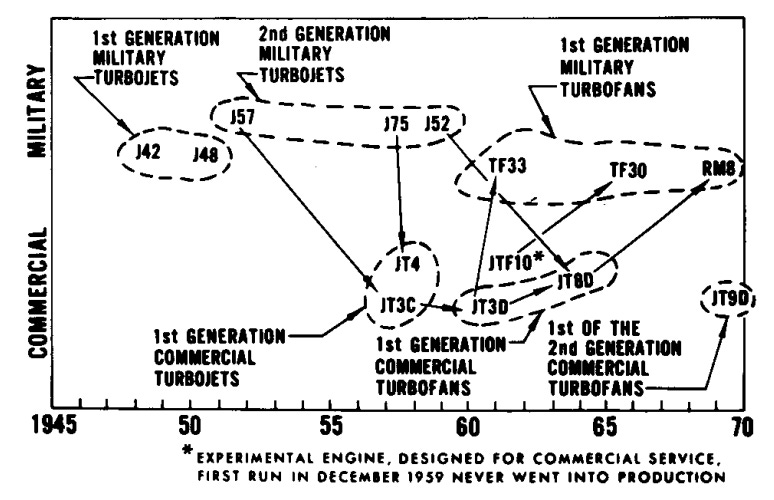

The US initially lagged in jet engine development, and the first US jet engine efforts relied heavily on existing British designs. The first jet engine built in the US, the GE 1-A, was a copy of Whittle’s W.2B/23 engine; the first mass-produced US engine, the J31, was derived from it. The prototype of the first successful US jet fighter, Lockheed’s P-80 Shooting Star, used a British H-1 “Goblin” engine (though the production version used American J33 engines).

But the US military quickly recognized the potential jet engines had for aircraft performance and began to pour huge amounts of money into companies like GE, Westinghouse, and General Motors to both build improved versions of British engines and begin developing their own models. The first US-designed jet engine, the Westinghouse J30, ran in 1943, and by 1950 the military had funded more than a dozen jet engine projects from a variety of manufacturers.

As money flowed into jet engine development, engine performance and technology quickly improved. Britain’s first production engine, a Rolls-Royce version of Whittle’s W.2B known as the Welland, produced 1600 pounds of thrust when it first ran in 1942. By 1950, the Pratt and Whitney J57 was producing 17,000 pounds of thrust.3 Thanks to better temperature-resistant materials, the turbine inlet temperature in the J57 was hundreds of degrees higher than in the Welland. And while early jet engines used centrifugal compressors that used a rotating impeller to push the air out to the sides, there were limits to how much these could pressurize air. By 1950 jet engines, including the J57, had almost universally changed to axial compressors, which compress the air along the length of the engine through a series of compression stages.

In addition to using axial compressors, engines further improved with the adoption of two-spool designs. The core of a basic axial compressor jet engine has basically a single large moving part: a rotating shaft with a turbine mounted on one end and a series of compression stages mounted to the other.4 With this arrangement, every part of the turbine and compressor spins at the same speed, but it’s often beneficial to have different parts of the engine spinning at different speeds: The low pressure front and high pressure rear parts of the compressor work most efficiently at different speeds, and it’s easier to maintain smooth airflow through the engine across a range of different conditions (and avoid things like compressor stall) if different parts of the compressor can rotate at different speeds.

One way of allowing different parts of the engine to rotate at different speeds is to add a second, inner shaft to the engine that rotates independently.5 The J57 was the first two-spool turbojet, and today most commercial jet engines use two or even three spools. Two-spool engine designs made it possible to achieve higher compression ratios and thus higher engine efficiencies. The Welland had a pressure ratio of around 4:1, while the J57 had a ratio of around 11.5:1.

But while by the 1950s jet engine performance had greatly increased, this was a hard-won achievement. Jet engines required a far greater understanding and mastery of the motion and behavior of hot gasses, and it took much more time to design them than piston engines. An executive at Pratt and Whitney noted that the J57 took on the order of 1.3 million man hours of design time, roughly twice as much as a piston engine did. And while piston engines could be made from comparatively thick and sturdy castings and forgings, much of a jet engine was made from thin sheets of exotic alloys carefully bent into shape, which required novel and complex manufacturing techniques. From “Dependable Engines: The Story of Pratt & Whitney:”

…the jet only became possible because of the development of alloys for that sheet metal that could handle higher temperatures and pressures. And Pratt had to figure out how to weld sheet metal. ‘With the multiplicity of joints in sheet metal parts of a jet, the distribution of stresses is one of the most important considerations. A weld becomes an actual design factor rather than a mere fastening device,’ Horner said.

He referred to many of the issues in converting to jets: things like relatively large diameter parts with very thin walls and all of the compressor and turbine components and airfoils with ‘a great variety of aerodynamic shapes of such awkward dimensions that our designers often complain that they have neither a beginning nor an ending.’

He called these ‘odd horses and peculiar cats in strange contrast to the piston engine’s comfortable old forgings and castings which were heavy and sturdy and supplied their own rigidity for machining.’ And all that sheet metal and oddly shaped stuff needed a lot of tools. To build the little J30, Pratt needed 5250 tools. By 1952 when Horner spoke, the J57 had 20,000 tools.

This complexity made developing a new jet engine difficult and time consuming. Early, centrifugal-compressor-based jet engines came together comparatively easily. The Rolls-Royce Nene, the most powerful aircraft engine in the world when it debuted, took just 5 months to go from starting design to a working engine. Axial-compressor-based engines, though capable of higher performance, were far more difficult to design and build because it was hard to ensure that the air flowed properly through the many different compression stages.6 Early jet engine designer Stanley Hooker noted that Rolls-Royce’s axial compressor engine that followed the Nene, the Avon, took seven years to iron out the various problems in it. GE’s first axial compressor engine, the J35, required a similar amount of time. And difficulty and time consuming meant expensive. Pratt and Whitney’s J57 took on the order of $150 million to develop, roughly $2 billion in 2025 dollars.

Among the successes of engines like the Avon, the J35, and the J57 were numerous failures. Westinghouse, one of the largest manufacturers of steam turbines, received a huge fraction of initial jet engine contracts and was poised to become a major jet engine manufacturer, but the company was unwilling to invest in the R&D necessary to master the new technology, and it struggled to produce reliable engines that met their performance targets. Westinghouse’s J30 engine suffered repeated development delays and problems that had to be fixed by Pratt and Whitney. When the engine was finally ready, it provided “only marginally satisfactory service”. It’s J40 engine had even worse struggles: a low-thrust version was delayed for three years, and a higher-thrust version was never successfully delivered at all. The J40 program, called “disastrous” and “a fiasco,” was ultimately cancelled.

Westinghouse wasn’t alone. Curtis-Wright, a major manufacturer of aircraft piston engines, ultimately secured 11 jet engine contracts from the US military by 1956, but the company struggled mightily to adapt to jet engine manufacturing. Its J65 and J67 jet engines were “persistently underpowered and failure-prone” even though the J65 was derived from an existing engine, and the company developed a reputation as “an engineering bungler”. One Air Force official described the company’s issues in a letter:

From the inception of the YJ and J65 programs there has been an apparent lack of appreciation by your management of the magnitude of the job you have undertaken. There has also been inadequate control over: tooling for the job, manufacturing processes and techniques, quality control, test programs, both at Wright Aeronautical and at subcontractors….

… Many of the theories presented by your Engineering Department in explanation for failures have proved to be unfounded. Engineering changes have been proposed and incorporated, in our opinion, to correct manufacturing [practice] deficiencies.

This was apparently just one “among scores of Air Force challenges to Curtiss-Wright’s ability to manage, and indeed even understand, the business of designing, building, and testing jet engines.” General Electric similarly struggled with its J33 and J47 engines. On the J33, Kelly Johnson (of Lockheed’s Skunkworks fame) complained about the engine’s “poor design features and poor maintenance,” noting that “Basic progress on flight investigations [for the P-80] has been very slow because of the inability to keep the airplanes flying.’’

Engine tail cones were cracking after 20 hours of use, and GE notified Johnson that replacing them would take two to three months. Turbine wheels were failing in 50 hours running or less, but GE was stalling on redesigns. Johnson railed about ‘the poor quality of the engineering design of certain engine changes,’’ ‘‘poor workmanship,’’ and the delivery of engines ‘‘unsafe to fly.’’

The J47 project, on which the air force spent $300 million by 1950 (~$4 billion in 2025 dollars), was extremely delayed and dogged by technical problems. Though the engine eventually entered service, poor reliability meant that it initially averaged only 11 hours of flight between major overhauls. Engines ultimately required extensive modifications, which had to be done in the field and cost millions. GE’s poor performance on the J47 project “discourage[d] Air Force optimism toward any new GE development.”

More broadly, while jet engines undoubtedly had high performance (the jet-powered F100, which first flew in 1953, was the first US fighter to break the sound barrier in level flight), it proved difficult to both constantly push the boundaries of performance and have engines that worked reliably and consistently. During the Korean War, an Air Force report noted that jet engine failures were the leading cause of major accidents: in 1951 alone there were 149 such failures, destroying 95 aircraft and killing 25 pilots. Engines were so unreliable that they made Air Force recruitment difficult: pilots “were no longer eager to join the Air Force if they had to learn to fly jets.”

The jet engine’s high performance made the military willing to fund development efforts and put up with its many shortcomings. But while those shortcomings might have been acceptable for military aircraft, using them on commercial aircraft would require further improvement. A commercial jet engine didn’t just need to meet its performance targets — it had to operate profitably.

Aircraft manufacturers started considering jet-powered airliners in the late 1940s, but initially few airlines were interested in them. In his history of commercial aviation, T.A. Heppenheimer describes the airline industry’s reaction to the jet:

…airlines, as commercial enterprises, in no way could accept the cost and performance limitations of jets. The jet engines that the airline executives knew about were still fuel-guzzlers, and aircraft that they powered would still be limited in range…And the jet engines of the day demanded much maintenance, which would drive costs even higher by taking aircraft out of service, reducing their ability to generate revenue. Ralph Damon, president of TWA, expressed a common view in the industry when he said, ‘The only thing wrong with the jet planes of today is that they won’t make money.’

Once again, the British took the lead. The British-built de Havilland Comet airliner debuted in 1952, powered by four de Havilland Ghost turbojets. And while the Comet ultimately failed (fatigue failures around its rectangular windows caused two crashes, resulting in it being withdrawn from service), it proved that jet travel, while expensive, could be profitable. From Turbulent Skies:

[The Comet’s] operating costs were nearly triple those of the [propeller-powered] DC-6. But it flew with nearly every seat filled, and though BOAC charged only standard fares, it found itself in the remarkable position of actually making money with the new jets. That brought other airline executives over for a look, including Juan Trippe [founder of Pan Am]. He met with Sir Geoffrey de Havilland, who was promising a seventy-six-seat Comet III, and in October he ordered three, with an option on seven more.

Trippe’s boldness gave other airlines no choice but to follow:

…while jets might offer dubious economics, their popular appeal was vivid and unmistakable. The Comet had shown that…This meant that once Trippe put jets into service, he could skim off the cream of everyone else’s business. Other carriers, particularly those serving the North Atlantic, would buy jets or lose their shirts.

In October 1955, Trippe ordered 45 jets for Pan Am: 20 Boeing 707s and 25 Douglas DC-8s. Both aircraft were powered by the Pratt and Whitney JT3, a commercial version of the J57.

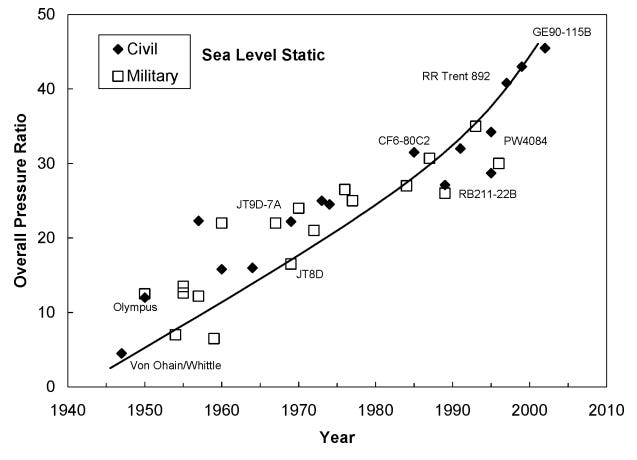

The demands of commercial service would continue to push jet engine performance higher and higher: Higher compression ratios and temperatures to minimize fuel consumption, and longer times between overhauls. This meant continually pushing the technology forward. For instance, early jet engines were made mostly from steel and aluminum, but by the 1960s they were being fashioned mostly from titanium and “superalloys” like Inconel. Turbine blades, already difficult to fabricate in the 1950s, got even more complex, with elaborate internal structures to allow cooling air to flow through the turbine blade.

Another key development for jet engine commercial use was the turbofan. In a conventional jet engine, all the air flows through the compressor, into the combustion chamber, through the turbine, and out the rear. This arrangement is known as a turbojet. But if you mounted a fan to the engine spool that was larger than the rest of the engine, some air would flow around the sides of the engine, rather than through it.

Adding this fan offers several advantages. On a turbojet, the hot exhaust exits the engine at a high speed, but jet engines are at their most efficient when the exhaust stream is as slow as possible. Air moved by the fan around the sides of the engine will be much slower than the hot exhaust from the combustion chamber, improving engine fuel efficiency. This slower air also makes much less noise — an important factor, since people were getting fed up with the noise from jets. A large fan also makes it easier to increase engine thrust, making it possible to power larger, heavier aircraft.

There’s a variety of different ways of adding a fan to a jet engine. GE added an aft-mounted fan to its CJ805 for use on the Convair 990 airliner. The company’s GE36 unducted fan, developed in the 1980s, also featured an aft-mounted fan. A turboprop, which mounts a conventional propeller to the front of the jet engine spool, is arguably a type of fan engine as well. But the engine arrangement that would be adopted for large commercial aircraft was a large, ducted fan at the front of the engine, an arrangement that became known as the turbofan. Today, virtually all large commercial aircraft are powered by high-bypass turbofans (engines where a very large fraction of air is routed around the engine rather than through it).

Fan engines had been proposed by Whittle when he was first designing his jet engine, and turbofans began to appear in the 1950s. Rolls-Royce introduced their Conway turbofan in 1955, and Pratt and Whitney introduced a turbofan version of their JT3 engine, the JT3D, in 1959. These early turbofans had relatively low bypass ratios (the ratio of air that goes around the compressor and turbine to the air that goes through it): The Conway had a bypass ratio of 0.3, and the JT3D had a ratio of 1.4. But by the late 1960s huge, high bypass engines were being built. Pratt and Whitney’s JT9D, the engine that powered the Boeing 747, had a bypass ratio of nearly 5:1, and GE’s TF39 had a bypass ratio of 8:1. (A modern LEAP engine has a bypass ratio of 10 or 11:1).

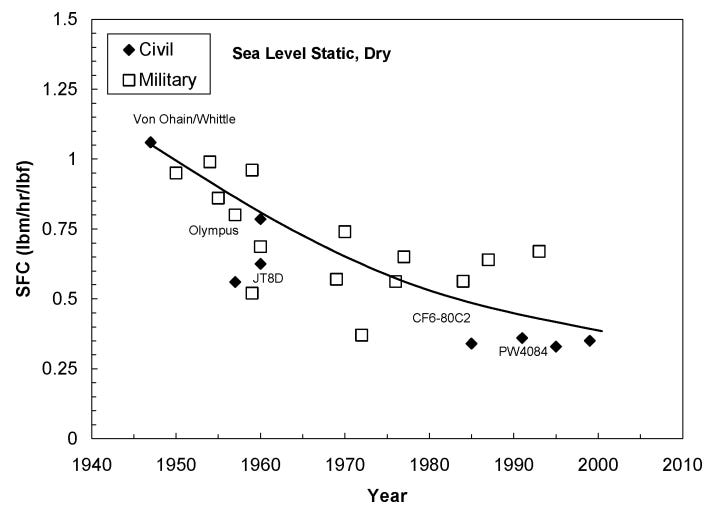

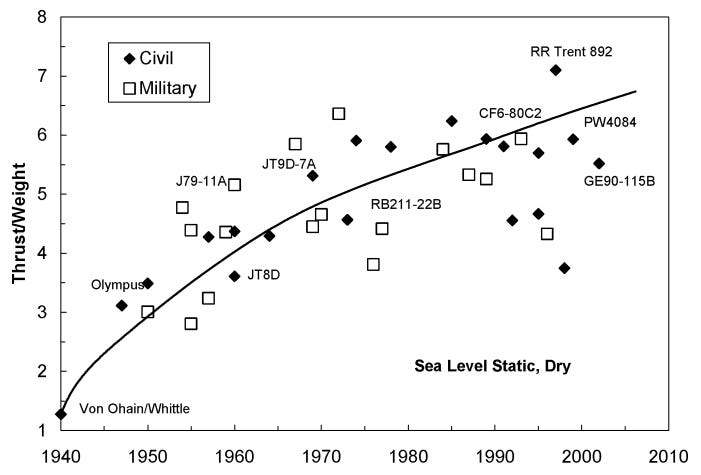

As a result of these and other improvements, engine performance continued to climb. Higher bypass ratios, pressure ratios, and turbine temperatures drove down fuel consumption, as did lower engine weight. Engine reliability improved, time between overhauls increased, and engine failures became much less common. While early jet engines needed overhaul after 10 hours of flight time, by the 1960s engines were operating for nearly 1000 hours before needing to be overhauled.

But this performance once again had to be fought for. By the 1970s, more than 30 years after the first jet-powered aircraft flew, it was still incredibly difficult and expensive to bring a new jet engine into service. Development costs were approaching a billion dollars: Rolls-Royce spent $874 million (close to $7 billion in 2025 dollars) to bring its RB211 into service, and delays and cost overages on the program bankrupted the company, forcing the British government to nationalize it. On GE’s TF39, development was plagued by early engine failures, and the engine repeatedly failed qualification tests. Pratt and Whitney had severe delays and problems during development of its JT9D, to the point where Boeing was forced to hang concrete blocks off the wings of completed 747s in lieu of engines which hadn’t yet been delivered.7 Once it was in service, the JT9D initially proved inefficient and unreliable, with a tendency to fail prematurely and to develop “surge” (a potentially dangerous phenomena where airflow reverses through the compressor). These problems took several years to iron out. Another Pratt and Whitney, the military F100 engine, similarly yielded “major controversy in the 1970s due to severe operational and reliability problems.”

We can get a better understanding of why, specifically, it’s so hard to develop a new jet engine by looking at the history of a specific one, the RB211. The RB211 is a high bypass turbofan engine designed and built by Rolls-Royce, originally for the ill-fated Lockheed Tristar. While the RB211 was ultimately very successful — Rolls-Royce sold 3760 of them, and the engine formed the basis for its current Trent line of engines — development took so long and went so far over budget that it drove the company into bankruptcy. Fortunately for us, the history of the RB211 is documented in a book published by the Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust, so we can see exactly what challenges had to be overcome to get it operational.

Design for the RB211 started in early 1967, with a team of 700 engineers. As designed, the engine would be a major advance over Rolls-Royce’s previous large turbofan engine, the Conway:

Compared to the Conway engine, the thrust was nearly double, the airflow was 3.7 times higher, the fan diameter was nearly double and yet the engine was marginally shorter. The pressure ratio at take-off had increased from 17:1 to 25:1 (27:1 at top of climb) and the turbine entry as designed was about 150 degrees centigrade higher at 1488 K on a hot day take-off. Climb and cruise temperatures were substantially higher. The weight of the basic engine (less power plant) was 8861 lbs compared with the 5160 lbs for the Conway.

To achieve the desired levels of performance, the RB211 had several novel features. Rather than using a two-spool design, it would use a three-spool, allowing further optimization of rotational speeds in different parts of the engine. To minimize weight, many parts of the engine, most notably the front fan,8 would be fabricated from composites like carbon fiber or glass-reinforced plastic. These and other improvements were estimated to reduce fuel consumption by 21% compared to the Conway, as well as reducing engine noise.

Initial design for the RB211 was completed by October of 1967, after which the company began to build the first engines for testing. If all went well, the engine’s first flight on a Lockheed Tristar would take place in November of 1970.

But when testing began in August of 1968, it was clear there were numerous problems with the engine. Examination of the engines following early tests showed that the combustion chamber lining was burnt and distorted, seals were breaking down, stators were cracking, and the layers of carbon fiber in the fan blade were delaminating. Guide vanes (airfoil structures which redirect the flow of air) were also cracked, and were burnt in some places and had rubbed against turbine blades in others. The engine had only produced around half of its design thrust, and engine surges had repeatedly occurred. As testing continued, problems mounted. By early 1969, 99 different major engine defects had been diagnosed. By September, the number of major defects rose to 175.

Slowly, meticulously, the design team pinned down various problems and reworked the design. Here are just a few of the problems that needed to be fixed:

-

In the compressor, glass-reinforced plastic parts such as the stators and the bearing housing, were replaced with more rugged (but heavier) metal ones. The high-pressure compressor drum was repeatedly redesigned to address air leakage, early failures, and problems of “ovalization,” and parts of the compressor were changed from titanium to an Inconel alloy. To reduce surge problems, a complex series of controllable guide vanes was added to the compressor. Compressor blades were strengthened to avoid premature failure and compressor guide vanes were changed from sheet metal to more robust forgings.

-

In the combustion chamber, the chamber lining was made thicker and generally strengthened, and the entire combustion chamber was redesigned to improve airflow and reduce air leakage at the turbines. A different heat treatment process for the casing was adopted, and a wire winding was added to the casing to prevent thermal expansion problems.

-

The secondary air system, which uses air to cool the engine, was completely redesigned to reduce leaks.

-

The carbon fiber front fan couldn’t be made strong enough to survive a bird strike, and was replaced with a titanium one. The fan case underwent multiple redesigns to be strengthened, which included changing it from aluminum to titanium.

-

In the turbine, the high-pressure turbine disk was changed from Nimonic to Waspalloy, another nickel-based superalloy. Gaps between turbine blades and guide vanes were enlarged to reduce vibration problems, turbine seals were redesigned, and cooling holes were added to the turbine blades. Turbine guide vanes were redesigned to improve cooling.

-

The engine was strengthened in spots to reduce vibration problems and related failures.

Diagnosing these problems and implementing the necessary changes took months of painstaking testing and experimentation: testing the engine, noticing the various failures, implementing fixes, and then testing the engine again. In some cases, engineers put enormous efforts into particular solutions, only to be forced to abandon them when they couldn’t be made to work. It wasn’t until 1970, for instance, more than two years after development began, that the carbon fiber fan blade was finally abandoned in favor of the titanium blade.

As time was spent addressing the various failures, the development schedule slipped:

By the end of 1969, 1,270 hours of bench running had been achieved against 3000 hours planned but, apart from the special run on Engine 7, no engine had run to 40,000 lb thrust and most engines had been removed from the test bed prematurely because of failure.

By the end of 1970, the program was a year behind schedule, and the launch costs of the engine had doubled. In early 1971, the company declared bankruptcy. But despite the setbacks, the team continued to work through problems: By the middle of 1971, “engines were not failing as frequently and hours were building up at a rate of 220 hours per month compared with 100 hours per month during the previous two years.” Performance improved, and thrust produced by the engine continued to creep up. By 1972, the engine was working reliably. It received its type certification in early 1972 and made its first commercial flight in April of that year.

This wasn’t the end of the troubles for the RB211 — it took 6 years after beginning commercial service for all the problems to be ironed out — but the end result was a successful engine, derivatives of which continue to be produced today.

Not all new jet engine projects will have the same struggles as RB211, but it’s been an expensive and time-consuming development task since the 1950s. The inflation-adjusted costs to develop a new jet engine have almost always run into the billions:

-

The J57, which powered the B52 and whose commercial iteration powered the first wave of US jet-powered airliners, cost roughly $2 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars.9

-

The J58, the engine that powered the SR-71 blackbird, cost closer to $7 billion.

-

Between the 1960s and early 2000s, the average inflation-adjusted development cost of a new military jet engine has been $1.5 billion.

-

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, both Pratt and Whitney and General Electric estimated that the costs of new jet engine development had reached $2 billion or more ($3-4 billion in 2025 dollars).

These huge costs mean that it can take 15-20 years for a new jet engine to make a return on its investment.

It’s not that building a jet engine that works is so difficult or expensive. Rolls-Royce built their RB178 demonstrator engine in the early 1960s for $84 million in 2025 dollars, roughly 2% of the RB211’s overall development costs. It started construction on the first RB211 engines just a few months after design began. Similarly, the technology demonstrator for GE’s TF39 engine cost $200 million in 2025 dollars, a small fraction of the full cost of the program.

The difficulty is building an engine that meets its various performance targets — thrust, fuel consumption, maintenance costs, and so on. There’s no point in designing a new engine if it doesn’t significantly improve on the state of the art, and that means engine development projects are constantly pushing technological boundaries: higher compression ratios, hotter temperatures, lighter weight, larger fans, and so on. An engine that isn’t an improvement over what’s already on the market won’t be competitive, and engine performance targets will often be contractual obligations with the aircraft manufacturers buying them.

Making these improvements requires constantly driving engine technology forward. Turbine blades, for instance, have been forced to get ever more advanced to withstand rising exhaust temperatures: modern turbine blades have elaborate internal cooling structures, are made from high-temperature superalloys like Inconel or titanium aluminide,10 and are often made from a single crystal to eliminate defects at material grain boundaries. And while the carbon fiber fan blades on the RB211 were unsuccessful, manufacturers didn’t give up, and such blades are used on the CFM LEAP engine.

Pushing boundaries means you’re operating in the unknown, encountering novel phenomena and unforeseen problems that take time and effort to fix: Many of the problems on the RB211 stemmed from Rolls-Royce’s lack of experience with the materials needed to withstand the higher engine temperatures.

This boundary-pushing is difficult partly because the requirements an engine must meet are very strict. A jet engine must direct and control an enormous amount of heat energy — a modern large jet engine will generate power on the order of 100 megawatts — and it must do so using as little mass as possible. A 1930s Ford V8 car engine weighed around 7 pounds for every horsepower it generated. A WWII aircraft piston engine weighed around 1 to 2 pounds per horsepower. The 50s-era J57 jet engine weighed closer to 0.1 to 0.2 pounds per horsepower it generated.

A commercial jet engine must operate for thousands of hours a year, year after year, before needing an overhaul, demanding high durability and high fatigue resistance. It must burn fuel at temperatures in the neighborhood of 3000°F or more, nearly double the melting point of the turbine materials used within them. Turbines and compressors must spin at more than 10,000 revolutions per minute, while simultaneously minimizing air leakage between stages to maximize performance and efficiency.

A commercial jet engine must operate across a huge range of atmospheric conditions – high temperatures, low temperatures, both sea level and high-altitude air pressures, different wind conditions, and so on.11 It must withstand rain, ice, hail, and bird strikes. It must be able to successfully contain a fan or turbine blade breaking off.

Ensuring the engine meets all these conditions entails thousands (or tens of thousands) of hours of testing, during which time the engine is subjected to a variety of punishing conditions. Testing for the CFM LEAP involved launching a 1 inch thick slab of ice directly into the front fan, and the engine had to continue operating while ingesting 3500 pounds of simulated hail. An engine must undergo hundreds of hours of in-flight testing, to see how it behaves across the flight envelope. When flight testing the LEAP engine, GE already had one test aircraft, a Boeing 747, but the in-flight testing was so extensive that it bought a second one.

In a domain where failure could kill hundreds of people, boundary-pushing performance and operating near the edge of what’s possible also means manufacturing must be extremely careful and precise. Small defects or failures that could be accommodated in other sorts of technology can be catastrophic if they occur in a jet engine. A mid-flight engine failure on a Rolls-Royce Trent-powered Airbus A380, where a turbine disk fractured and ripped apart the entire engine, was traced to a single oil pipe manufactured with a wall that was half a millimeter too thin. Pratt and Whitney has lost billions of dollars correcting manufacturing defects in its Geared Turbofan that resulted from a “microscopic contaminant” in the powder used to manufacture turbine disks.

All this makes a new jet engine project incredibly risky. To mitigate this risk, manufacturers try wherever possible to leverage the technology they already have, minimizing the new and unknown (and also reducing the cost of things like certification testing). Commercial engines are often derived from military engines, where the government has already picked up the tab for development delays and cost overruns. GE’s TF39, designed to power the Lockheed C-5 military transport, evolved into the commercial CF6, and CFM’s successful CFM56 engine used the engine core (the compressor, combustion chamber, and turbine) developed for the B-1 bomber. Pratt and Whitney’s military J57 became the commercial JT3.

Engine manufacturers will also often try to improve performance of existing engines rather than developing all new ones from scratch. Rolls-Royce is still building off of the RB211, an engine first designed nearly 60 years ago. And the Rolls-Royce Olympus engines that powered the Concorde in the 1970s were scaled-up versions of an engine originally designed in the 1940s.

Like with commercial aircraft, it’s much easier and less risky to stretch and improve an existing engine design rather than start a new one from a clean sheet, and only the potential of huge performance gains can justify the latter.